The amount of time spent on each step of the software development life cycle varies from project to project. However, the implementation phase is always the most significant portion. That means this is the area where projects can fail or succeed. We can ace all of the other steps in the life cycle, and a mediocre implementation will wipe out all that good work.

Balance The Effort

In my experience, the most impact during implementation is to try for a balanced effort from start to finish. Avoid a slow start and then hectic finish to hit deadlines. Particularly for longer stretches of implementation and big projects. This is a killer of productivity and quality. I have seen project after project that burns out team members with a hard push at the end that could have been avoided. The way to accomplish this is to set proper milestones and goals that balance the effort throughout the phase. When you keep the goals in sight, it is easier to keep everyone focused and avoid the lazy drift big projects see at the start.

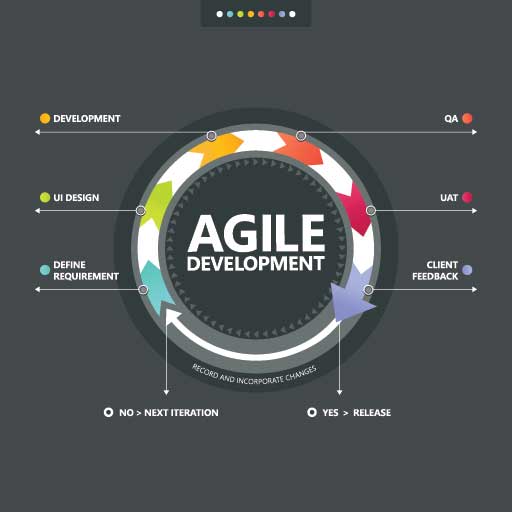

Regular Sanity Checks

Another essential trait of a successful implementation phase is regular checkups. These are not progress focused as much as they are about requirements. There are a variety of ways to do this, but the result should be a review of what is being implemented to ensure it is still in line with the requirements. This includes reducing feature creep as well as correcting design drift. Short projects will not suffer from this too much. However, long-term or large projects can see dramatic implementation problems and slipped dates from adding features or skewed solutions to requirements.

The good news is that this task does not need to be done by the implementation team. Team members from other phases (or QA staff) can perform sanity checks of features. They can measure against requirements and then meet with the implementation team to correct problems.

Frequent Code Commits

This may seem minor, but regular code commits are critical. I have come across numerous projects that tank because of impossible code merge needs, or a team member disappears along with their source. Ideally, this is built into the daily regimen of the implementation team. Regular merge and build steps are a big help as well. Much like the sanity checks above, regularly testing that you have all you need for a successful build helps keep from drift. This factor is a solid argument for best practices like continuous integration and regular builds.

Test Early

Testing has gotten better but still is too often left to the end of the project. This is when the cost to correct errors is at the highest level. It has been established over the years that the earlier a bug is detected, the easier it is to fix. There is a bit of a challenge in early testing as (by definition) the implementation is not yet complete and ready for full testing. This timing also means that there will be more time spent testing than when it is held until the end. That is entirely ok. The more testing that can get done, the more likely bugs will be found and squashed.

When you combine early testing with regular builds and commits you get feedback early, and quality is built in from the start. This approach even makes the testing process better. The test scripts and tools can be used and refined during the implementation phase to improve coverage and confidence in the results.

Note that none of these improvements are substantial on their own. These can be implemented as part of the process and pay worthwhile dividends when the project completes. All of these can also be tried out to see how they work for you. When in doubt, give it a shot and verify for yourself whether these are good for your team.