The Agile manifesto started an entire industry. It has even been the focus of numerous “religious” debates and arguments. However, it has a lot of wisdom within it that is often overlooked. The main ideas are as relevant today as they were when it was first crafted. Therefore, it is worth our time to review some of these wise nuggets and consider applying them throughout our software development efforts.

The Manifesto Is Not The Agile Methodology

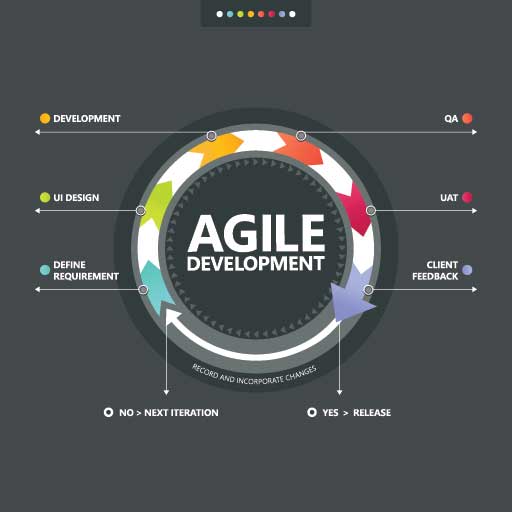

We need to start by clarifying that the Agile Manifesto is not the same as the Agile Methodology for building software. The manifesto was used to create the methodology. However, they are not one and the same. Think of the methodology as an attempt to turn the manifesto ideas into reality. It is easy to see where many agile or extreme programming techniques got their start in the manifesto. Nevertheless, your opinion (and experience) of one may be noticeably different from the other.

The manifesto came out of a desire to create better software. The first point drives that concept home. The highest priority is to satisfy the customer. This statement should be the “why” of any application and cannot be turned into a process. The Agile methodology provides a lot of ways to assist in this goal but does not guarantee it. Looking at it that way, we can easily see where a team could use Agile methodology precisely as described and still fail to deliver a successful project.

Work As A Realist, Focused on Delivery

There are twelve points the Agile Manifesto lays out. These emphasize producing a solution the customer wants while acknowledging the realities of software development. The most important of these practicalities, to me, is delivering results along the way to the final solution. This process recognizes that customers often change their minds, communication problems exist, and showing is better than explaining.

We all know there is often a disconnect between business representatives and technical resources. The language does not always translate and skilled liaisons are in short supply. Thus, we can lower the bar by deciding to be flexible from the start. This approach is not a way to ignore requirements gathering, design, or other due diligence. Instead, it assumes we will need to revisit those steps.

The Manifesto Points

Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.

Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.

Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.

Working software is the primary measure of progress.

Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.

Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility.

Simplicity–the art of maximizing the amount of work not done–is essential.

The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

The Agile Manifesto

Work Together For A Common Goal

There are numerous rules of software development built into this manifesto that are needed for a successful product. We already stated a focus on making the customer happy. This statement is not arguable. A product that does not please the customer is a failure by definition. Another important concept that is woven throughout the manifesto is the Pareto Principle. This rule says that 80% of our effort is spent in the last 20% of the product. That means we can get “mostly there” relatively quickly. This focus on getting most of the way to the solution is highly valuable.

Let’s think about that a bit. When you are almost done, you likely have a lot of the core functionality covered. The “happy path” is complete and functional. That is an essential factor in getting feedback. You have a use for the product the customer can see and experience. They have something concrete to assess and a solid basis for requesting changes.

Gaps In Knowledge

It is not very different from taking a vehicle for a test drive. You can get a feel for it and might even see some weaknesses. This last factor is critical to the success of a product. Customers should not be required to know edge cases and outliers in building a solution. That is up to the developers. However, these are issues that often fall into the “you do not know what you do not know” category. When you provide a demo or partially complete solution, you give the customer a straw man to work with. That is far more concrete and relatable than describing functionality or showing them a flow chart.

Keep It Simple Somehow

The focus on delivering regularly and the underlying Pareto principle ideas lead us to opportunities for the KISS approach. It is amazing how often customers will scope out requirements to get working software in their hands sooner. This carrot is dangled in front of them during regular demos and releases. Yes, there are gaps. However, a good relationship with a customer can lead to a shorter path to something they want and consider “done.” Who would argue against that?

Remain Flexible

The last central theme I want to point out is the focus on change. When we create software, it is crucial to think about flexibility. We are not building a system to solve a specific problem and situation. Instead, we are trying to provide a solution that is useful in a broad range of configurations. The world is also constantly changing. Therefore, even though we can be assured of a need for new versions of our software, we need to be smart about it. A sound system is built with growth and change assumed. That means we need to prepare for it from the architecture through to each step of implementation.

The Agile Manifesto has been around for many years. Nevertheless, it still is needed to remind software developers and teams of what is important. When we embrace these core concepts it reduces risk and improves our chances for success.